Britannia Works, Colchester

For forty years, from 1941 to 1982, Paxman occupied Britannia Works in Colchester as well as its main Standard Works site on Hythe Hill. The history of Britannia Works stretches back long before Paxman's involvement. Its early history provides interesting insights into engineering activities in Colchester during the nineteenth and early twentieth century including some connections with Paxman.

Sadly Britannia Works is no more. The site, behind St Botolph's Church and St Botolph's Station (Colchester Town), is now a car park. Some photographs of the Works can be seen on the page Britannia Gallery.

The History

The earliest mention of the site dates back to 1811. It was used by a William Dearn who was a nail maker. Irish by birth and an ex-army officer, he lived in Magdalen Street.

In 1827 the Works became St Botolph's Works, taking its name from nearby St Botolph's Priory.

From 1836 (Andrew Phillips suspects as early as 1833) the Works was used as an iron foundry as well as for nail making.

William Dearn died in 1859. His son, also called William, took over the business and called it an ironfounders. Examples of his work can still be seen in the locality. They include the iron gates for the Stockwell Street entrance to the Town Hall Law Courts and items in Nayland village such as the gates to Nayland Church. More mundane items produced by the foundry were fire grates and drain covers.

William Dearn junior continued to run the business after his father's death, with a workforce of four men and a boy, until his own death in August 1866. However, because of bankruptcy, the premises were sold over his head in September 1860 for £1,610, to Joseph Blomfield, a Colchester ironmonger who had a shop in nearby St Botolph's Street. (1) Among other things Blomfield sold Wheeler & Wilson sewing machines. When the patent on these expired Blomfield was approached by Thomas Mayhew Bear, an able engineer and experienced ironfounder from Sudbury, with a view to entering into partnership and making sewing machines themselves. They formed the Britannia Sewing Machine Company. This was so successful that when William Dearn junior died Blomfield and Bear relinquished all their general foundry work and sold the stock, patterns and goodwill to Davey, Paxman & Davey who had recently set up in business. (2) In 1871 the Britannia Sewing Machine Co employed 105 people but by the 1880s faced overwhelming competition from the Singer Sewing Machine Company of the United States. It therefore turned to manufacturing other products, mainly machine tools and oil engines. (3)

Colchester Ironfounders

In the later part of the nineteenth century there were several ironfounders in Colchester. A 1971 survey found that cast iron street lamps and furniture within 300 yards of St John's Green carried the names of no less than six local foundries. These were Bennel, Brackett, Catchpool, Mumford, Truslove and Stanford. Brackett is still a going concern in Colchester, now manufacturing large water strainers and filtration equipment.

Catchpool has a Paxman connection in that James Paxman joined the firm of Catchpool & Catchpool in 1851 at the age of 19. At the age of 21 Paxman was appointed Managing Engineer of the firm but perhaps gilded the lily by claiming in later life that he was Works Manager from that age. Subsequently he was appointed Foreman, a position in which he was effectively Catchpool's Works Manager, until leaving in 1865 to start his own business with the Davey brothers. (4) The Catchpool firm became Catchpool & Thompson in 1858 when Henry Thompson was taken into partnership. (5) As an aside, it is interesting to note that Henry Thompson's sister, Mahala, married James Howard of Bedford, the head of an important family firm of agricultural implement makers which in the 1920s was a member of the ill-fated Agricultural & General Engineers combine, as was Davey, Paxman & Co.

The name Mumford also has a Paxman connection. Shortly after Davey, Paxman & Davey established their business in Culver Street, James Paxman allowed Arthur G Mumford to share part of his Works. When Paxman moved to its present site in 1876, Mr Mumford took over the whole of the original Standard Ironworks and flourished as a manufacturer of marine engines and pumps until 1933.

. . back to Britannia's history

In the 1870s the business started selling small drilling machines, fretworking machines, and small lathes, etc. These were mainly aimed at small businesses and private workshops. Another product line was velocipedes, an early form of bicycles. During this period the Company dropped the Sewing Machine part of its name and became The Britannia Company.

In the 1880s the Company started production of larger industrial lathes. Some particularly large ones were produced by it for James Paxman's business at Hythe Hill. They also manufactured treadle operated drills for dentists.

In 1893 the Britannia Company built some oil engines which were exhibited at the Royal Show. In doing so it was nearly ten years ahead of Paxman, which did not have an oil engine on the market until 1904.

By 1898 Thomas Bear was a sick man and James Paxman made a bid for his business but this proved unsuccessful.

By the early years of the 20th century the firm was in difficulties. In 1903 the business was bought by the Nicholson brothers, Victor, Hugh and Percy, (6) who changed its name to The Britannia Engineering Co Ltd. The following year they introduced the Britannia motor car. Some publicity literature of the time carries a picture of the 'Britannia' four cylinder 18-24 hp engine and a guarantee 'to replace in our Factory, Free of Charge, . . . any part manufactured and supplied by us, found within six months after delivery to be defective in material and workmanship'. The guarantee did not extend to consequent damages or expense! The cars were of a conventional design for the period but sales were poor as they were neither well made nor reliable. The Company ceased manufacturing them around 1907/8.

About this time the Company designed a 2 foot gauge motor locomotive. John Browning of Queensland emailed the following extract from the Australian Sugar Journal of April 1910: "In view of the heavy cane crop at Habana, the Pleystowe Central Mill Company have placed an order with Messrs Smellie & Co of Brisbane for a 15hp petrol locomotive for haulage of cane to the mill. The Britannia Engineering Works, Colchester, England, have designed this locomotive. It has two forward speeds and two reverse. It can haul 24 tons on the level. The total weight is only 35 cwt." Pleystowe is just outside Mackay in coastal Queensland. As yet there is no confirmation that the locomotive was actually built.

Britannia Works closed around 1912 but the start of World War I brought a new lease of life. It reopened in 1914 to manufacture munitions and war supplies which put the business into profit. Still owned by the Nicholsons, the business was operating again in 1918 as the Britannia Lathe & Oil Engine Co Ltd. (7) It reverted to the production of metal turning lathes for which it became world famous. In an advertisement which probably dates from this post First World War period, the company offered a 4½" Standard Lathe, incorporating 'Many Improvements', for £34:0:0. A limited number were available on easy payment terms - an £8:10:0 deposit and 'the balance spread over a long period'.

During the late 1930s Britannia's business again declined. This led to closure in 1938, after which the Works stood derelict.

The Paxman Era

With the outbreak of war the British Government needed large numbers of powerful, yet compact, prime movers. Petrol engines were available which could have met the power to weight requirement. However in some of the envisaged applications the engines would be installed in confined spaces where the fire risk associated with petrol was a major disadvantage. There was very little choice of suitable compression ignition engines which, because of their much lesser fire risk, were the preferred alternative. One engine, however, did meet the requirement. The Paxman 12 cylinder VEE RB was already well developed and of proven performance.

A further Government requirement was that the engine should be suitable for manufacture on a large scale. Edward Paxman and his team of designers, led by Albert Howe, modified their existing engine for the purpose and so the 12 cylinder TP and TPM were born. Instead of having the crankcase and cylinders in one large and relatively complex casting, this was split into three pieces (hence the name 'TP' according to one source) comprising the crankcase and two separate banks of cylinders. Many more firms would be capable of making these smaller and simpler units on a sub-contract basis. Indeed an important element of the design philosophy was that all the engine's components should be capable of being manufactured in small workshops up and down the land. This would make it easier to find the necessary manufacturing capacity as well as reduce the risks of major disruption if a factory was bombed.

Paxman's Hythe Hill factory was already working at full capacity. An order for engines for 'U' Class submarines had been followed by another engine order for 'S' Class submarines. This was on top of existing production of engines for destroyers, cruisers, corvettes and frigates, generating sets for the army, tank sprockets, mines and paravanes. The Ministry of Supply, which controlled all diesel production in the country, therefore leased the Britannia Works in 1941 to provide Paxman with space to build its TP engines. The Company was appointed to manage it and at once started reconstruction work, laying down storage space, test beds, cooling water mains, and generally strengthening the original wooden structure.

The Ministry of Supply enlisted over 400 engineering concerns, large and small, to produce the 1,300 or so different components required for the engine. Multiple sets of jigs and tools for the manufacture of each component were designed and made by Paxman at Colchester for issue to the sub-contractors' workshops. The parts they produced, a total of 5,000 for each 12TP, flowed into the Britannia Works where the engines were assembled. The 12TP/12TPM was designed to be simple to produce, a necessity with wartime labour shortages. Eighty five percent of the staff taken on to build the engines were unskilled and mostly women. They also tested each engine prior to despatch.

The Nellie Project - Churchill's Trench-Digging Machine

The first call for the 12TP was as the propulsion engine for a large tank needing 600-650 hp where an absolute minimum of space was available. It has been argued that the TP designation stood for "tank propellant", and not "three pieces" as suggested elsewhere. Two TPs were supplied for the prototypes of the tank, the story of which is told on the page Paxman's Tank Propellant. The next call for the TP was to power a very large trench-digging machine, the brainchild of Winston Churchill. According to one source the first bulk order for TPs was one of 550 engines for this machine and the tanks.

The construction of the French Maginot and German Siegfried Lines during the inter-war years led to an assumption that any future conflict would again involve trench warfare. Mindful of the appalling loss of life in the trenches of 1914-18, Churchill wanted to find a way of allowing troops and supplies to advance in relative safety and quickly break through the German front line. He came up with the idea of machines which would dig large trenches through No Man's Land under cover of darkness and the noise of an artillery barrage. Troops and tanks would follow in these trenches, coming to the surface at or behind the enemy front line. Churchill was unsuccessful in his attempts to persuade the army to take up the idea. However, in September 1939 he had been appointed First Lord of the Admiralty and as such had all the resources of the Navy at his disposal. He arranged the setting up of a secret department, under the Department of Naval Constructors, to design his trench-digger or 'mechanical mole'. This Department of Naval Land Equipments designed the prototype which was dubbed 'Nellie', a name derived from the department's NLE name. In Paxman's Drawing Office the NLE machine was referred to as the 'No man's Land Excavator' - a very apt description. The project was surrounded by great secrecy and the actual name given to it initially was 'White Rabbit 6', later changed to 'Cultivator 6'.

On 7th February 1940 Cabinet and Treasury approval was given for the construction of 200 narrow 'infantry' machines and 40 wide 'officer' machines. The 'officer' machines were intended to dig trenches wide enough for tanks to travel along. The original planned production rate was 20 machines (requiring 40 engines) per week. In its final form the prototype, 'Nellie', was 77' long, 6' 6" wide, 8' high and made in two sections. The main section, driven on caterpillar tracks, looked like a greatly elongated tank and weighed 100 tons. The front section, weighing another 30 tons, was capable of digging a trench 5' deep and 7' 6" wide. It comprised a plough which cut the top 2' 6" of the trench, and 'pick and shovel' cutting cylinders which excavated the bottom 2' 6". The spoil was carried away by conveyors to the top of each side of the trench to create 3' parapets. Nellie could move at just over half a mile an hour, removing some 8,000 tons of spoil in the process. When she reached the enemy's front line she would stop and act as a ramp for following tracked vehicles to climb up out of the trench onto open ground. Originally she was to be powered by a single 1,000 bhp marine version of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. Apart from the fire risks inherent in a petrol engine, it was soon pointed out this engine could only be expected to produce 800 bhp under continuous load, less than was required for the task. Shortly after, all Merlin engines were urgently needed by the RAF and Sir Harry Ricardo's advice was sought on a suitable alternative. He recommended using two Paxman-Ricardo engines of the type already in service with the Navy and of a proven design. The decision was made to use two 600 bhp Paxman 12TPs, necessitating a complete redesign of Nellie. One engine was to drive the cutter and conveyors at the front and the other used to propel the machine itself.

Winston Churchill witnessing trials of 'Nellie' at Clumber Park in November 1941.

The war very quickly took a totally unexpected course. After Dunkirk and the fall of France the trench-digger project collapsed. Large scale production of TPs for it was abandoned and the engine capacity was turned over to the Admiralty. Field trials of the pilot machine, which was built by Ruston-Bucyrus at Lincoln, were conducted at Clumber Park in Nottinghamshire. These commenced in June 1941 and were not completed until about January 1942.

The most detailed history of Churchill's trench digger is 'Nellie' - The History of Churchill's Lincoln-Built Trenching Machine by John T Turner, published in 1988 by The Society for Lincolnshire History & Archaeology (ISBN No 0 904680 68 1). It is a very well researched and written publication. According to this history only five of the smaller 'infantry' version of the trench-digger were actually completed. Four were scrapped at the end of the war and the fifth, believed to have been the pilot machine, was scrapped in the early 1950s. There is a suggestion that work was commenced on four of the wider 'officer' machines but that these were scrapped when Winston Churchill finally agreed to cancellation of the project in May 1943.

Engines for Tank Landing Craft - The 12TPM

After the fall of France in 1940 the Admiralty was very conscious that sooner or later troop and tank landings would have to be made in occupied countries. Tank Landing Craft and suitable engines for them would be needed in great numbers. The TP was quickly adapted to meet the Ministry of Supply's requirement for marine propulsion units. The 12TPM version of the engine featured a deeper sump, water-cooled exhaust, marine gearbox, etc. Thus Britannia Works became even more important to the war effort, being both the main production facility and the control centre for all TPM engines. TPMs powered virtually all British-built Tank Landing Craft used in the Second World War, seeing service at Dieppe, North Africa, Sicily, Italy and the Normandy landings.

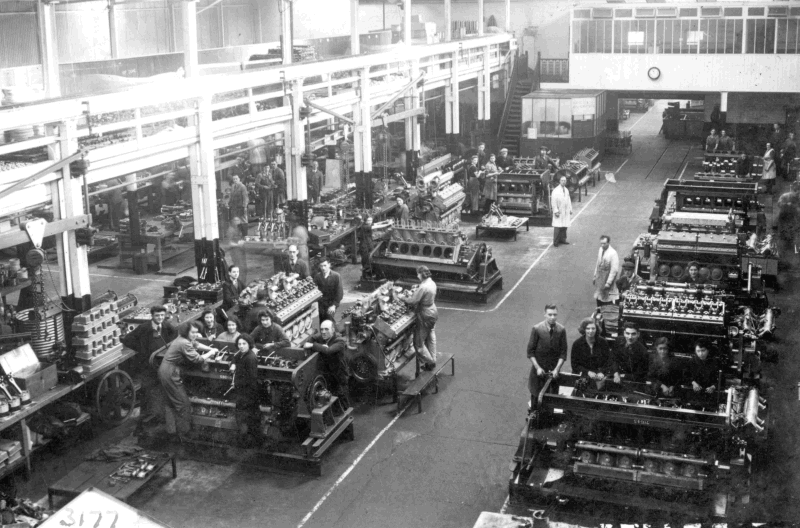

12TPM Engine Assembly at Britannia Works in December 1942.

As can be seen in the picture above, a large proportion of those working on TP engine assembly were women.

Women formed a major and vitally important part of Paxman's workforce during the Second World War.

Orders for the 12TPM eventually reached 4000 but by the time 3,533 had been delivered the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki finally brought the war to an end, making further production unnecessary. 2,227 TPMs were built and tested at Colchester's Britannia Works. The other 1,306 were built at Renault's British factory at Western Avenue, Park Royal, London W3.

Britannia Works also provided a reconditioning or overhaul service for TPM engines. After delivery back to the Works, they were stripped down to component level for degreasing and cleaning. The parts then went through inspection before being passed for re-assembly. The engines were rebuilt to 'as new' standard even though in most cases they had run far in excess of the planned hours between overhauls.

Incendiary Bombs Hit Britannia Works

The Works suffered serious fire damage from incendiary bombs on the night of 22nd-23rd February 1944. The report of the incident from Sector Captain 232 to the Fire Guard Officer, Colchester, gives a vivid picture of a hectic night of firefighting:

REPORT FROM SECTOR 232

ON INCIDENT OF TUESDAY 22ND FEBRUARY 1944.On the night of Tuesday, the 22nd - Wednesday 23rd, Sector point 232 was manned by Deputy Sector Captain T. Watts, at Britannia Works, who has supplied the following information.

Alert was sounded at 11.54 Tues. 22nd, when Messrs. Blomfields reported 1 party for duty, sector point strength was 3 Stirrup Pump Parties, 1 Wheelbarrow Pump Party, and 1 Light Trailer Pump manned by works Firemen. No reports received from Messrs. Luckings and St Botolph's Station.

Incendiaries fell in sector at 12.25.a.m. our own works being heavily hit.

The Fire Guards tackled them with vigour, but owing to the large amount of incendiaries dropped, were unable to cope with the situation, and Britannia party leader called in Works Fire Brigade at 12.33.a.m.

The Ld/FM in charge immediately called for N.F.S. assistance owing to the great risk involved, and message left sector point at 12.40.a.m. Up to this time, and at no time during the incident were any other calls for N.F.S. assistance received at sector point.

Message to N.F.S. Station I.V. Magdalen Street was carried by Deputy Sector Captain T. Watts, who detailed R. Wright Night Gatekeeper to receive all messages in his absence, and owing to the conflagration near Messrs. Cheshires premises his route was via Station platform into Magdalen Street. Upon arrival he was informed "No pumps available at the moment", and returned to Sector Point.

I was called to sector point by Deputy Works Superintendent, Mr Napper, by telephone, and arrived at 1.25.a.m. Wed. 23rd. On arrival I noticed a large section of the sector was a mass of fire, including a section of our own works. I first checked up on our own position, and contacted Mr. Short, Admiralty Fire Inspector who was assisting the operations at the works. I then proceeded to inspect the rest of our sector and found the N.F.S. had taken charge at Messrs. Blomfields, and Cheshires, so then concentrated on saving as much as possible of our own works.

The N.F.S. arrived via Priory Street at 3.00.a.m. and by this time our water supplies were almost exhausted, so I then arranged a water relay from Marriages Mill, and personally conducted them as they were strangers to the town; relay was working at 3.30.a.m. approx., and fire was under control at 6.30.a.m.

I would like to place on record the fine work done by Fire Guards in assisting our Firemen in all various forms, also the Fire Crew from Messrs. Days Transport who came and kept us supplied with water at the most critical time when our supplies were almost exhausted, also the help we received from Fire Crew Standard Ironworks, and St. Botolph's Station, members of the Home Guard, and Wardens Service.Sector Captain

Britannia Works after the fire - St Botolph's Church in background.

For more photographs go to Britannia Gallery

After the fire Britannia Works was rebuilt in five months, during which time TPM production continued at the rate of over 30 engines per week.

The Post-War Period

After the war production of components and associated control gear for engines continued at Britannia Works and Paxman eventually purchased the premises.

One of the activities carried out in the late 1940s was the building of small stationery Ruston engines.

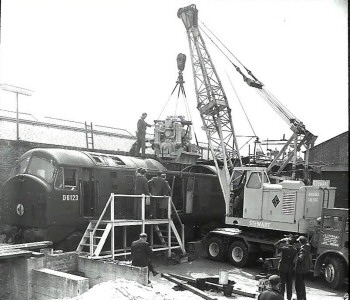

About 1951-52 Paxman's Development Department was moved to Britannia Works to release more space for production at Standard Works on Hythe Hill. One development project undertaken at 'The Brit' around 1962-63 was to establish a method for re-engining some British Rail Scottish Region Type 2 locomotives. These had originally been equipped with a competitor's engines which had proved unsatisfactory in service. Paxman won the contract to supply Ventura 12YJXLs to replace them. In 1963 one of the locos (D6123) was brought down to Colchester for the fitting of the first of these Venturas. Britannia Works was ideal for the purpose as it already had a spur from the main rail network which enabled locos to be brought right into the Works. It also housed the necessary development staff and equipment, such as overhead cranes, essential for such a project. Once the method had been proved the remaining twenty locos were re-engined at BR Scottish Region's Polmadie Works.

About 1951-52 Paxman's Development Department was moved to Britannia Works to release more space for production at Standard Works on Hythe Hill. One development project undertaken at 'The Brit' around 1962-63 was to establish a method for re-engining some British Rail Scottish Region Type 2 locomotives. These had originally been equipped with a competitor's engines which had proved unsatisfactory in service. Paxman won the contract to supply Ventura 12YJXLs to replace them. In 1963 one of the locos (D6123) was brought down to Colchester for the fitting of the first of these Venturas. Britannia Works was ideal for the purpose as it already had a spur from the main rail network which enabled locos to be brought right into the Works. It also housed the necessary development staff and equipment, such as overhead cranes, essential for such a project. Once the method had been proved the remaining twenty locos were re-engined at BR Scottish Region's Polmadie Works.

Left: The 12-cylinder Ventura engine being installed in D6123 at Britannia Works in 1963.

Production of engine governors, under the name of Ardleigh Engineering which later became Regulateurs Europa, moved from Hythe Hill to Britannia Works in about 1956/57.

Britannia Works as at 1965

To mark Paxman's centenary year in 1965 the Essex County Standard published a commemorative supplement. In it the Company's General Works Manager, B R (Bob) Bensly, describes, among other things, the several different functions then carried out at Britannia Works. Britannia was responsible for a large proportion of Paxman's machining activities, including the manufacture of all cylinder heads and blocks. Within another specialist department vast quantities of smaller component parts were machined from bar material. The works was also responsible for producing the majority of spares required for those Paxman engines no longer in current production.

A different area of work was the manufacture of an extensive range of precision hydraulic control equipment, including engine governors. This was effectively the production facility for Regulateurs Europa, Paxman's governing and control business. It was transferred to RE's new works in St Leonards Road, next to the Standard Works site, in 1965.

Other departments at Britannia were Development, with its engine test beds, and RO which handled major repair and overhaul of customers' engines. From this we can see Paxman's second works formed a substantial part of the Company's manufacturing facilities in the mid-1960s and carried out a remarkably diverse range of functions.

The Final Years

Up to the closure of Britannia Works in 1982, both the Development and Repair & Overhaul (RO) departments remained here. RO was located at the bottom of the Works. In the late 1970s some machines were transferred from Standard Works for machining cylinder head and other small components, and from that time cylinder heads were assembled at Britannia in the lower part of the middle bay. The building right behind St Botolph's church became a Ministry of Defence bond store for Paxman spares purchased by the MOD. In the railway bay were some packers who made boxes for spares, for the bond store, and probably for the RO section. The Development department shared offices with internal printing, tracers and the Works photographer. It is said the offices were stifling in the summer and freezing in the winter but that the wildlife was amazing. Tree creepers used to work the pear trees, foxes were common, one day a small deer appeared and even a pheasant.

After a long and eventful history the Works closed in 1982. The building was demolished in 1987 and the site is now the Britannia car park. A short distance away, close to Colchester Town railway station and opposite the entrance to the new Magistrates' Courts, a crankshaft from a 1946 Paxman RPH engine now stands on a plinth as a reminder of the old Britannia Works and Paxman's activities there.

References and Further Reading:

1. Steam and the Road to Glory, Andrew Phillips, Hervey Benham Charitable Trust 2002, ISBN 0 9529360 1 1. p.39.

2. ibid. p.66.

3. A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9: The Borough of Colchester (1994): Modern Colchester: Economic development, pp. 179-198. www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=21987

4. Steam and the Road to Glory, pp.26,27.

5. ibid. p.32.

6. A History of the County of Essex: Volume 9: The Borough of Colchester (1994): Modern Colchester: Economic development.

7. ibid.

Acknowledgements: I am indebted to the late Denis Turner, formerly Applications Engineering Manager at Paxman, and to the late Michael Johnson, former custodian of the Paxman Archive, who provided material for this page and patiently fielded my many questions. Also to Marcel Glover, formerly Senior Development Engineer, MAN B&W Diesel Ltd, Paxman who provided the photographs on this and the Britannia Gallery page and information about the final years at Britannia.

Page updated: 09 Oct 2024 at 12:22