CHAPTER ONE

The Making Of The Man

'Poor little Louisa,

Her sisters do tease her,

They seldom do please her,

That little Louisa!'

(Childhood poem about Rudston attributed to Marjorie)

Louis Frederick Rudston Fell was the child of a marriage between two families who made their fortunes during the industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and used their riches to buy land. Both families grew rich from textiles (the Fells from cotton; the Pickersgill Cunliffes from silk); commodities that were at the forefront of the industrial revolution. The incomes of such families collapsed with the onset of free trade and cheap transport across the Atlantic, and those that could not learn how to cope with the nineteenth century agricultural recession by effective farming of their land got into trouble. They maintained their status by selling blocks of land rather than making money out of farming that land - and of course eventually they ran out of land to sell. Today, like most of us, their descendents have to live on what they can earn with their own wits.

Rudston's father, Lt. Col. William Edwin Fell, came from the older of the two families. He appears, with his own descendants, in Burke's Landed Gentry as a descendant of the Fells of Lismore, where his lineage can be traced back to the sixteenth century. His mother Barbara had re-married after his father's death, and his step-father Thomas Wead was rector of Withyham, a village just to the north of Crowborough in East Sussex. It seems that William had lost most of his material assets when he met Alice Pickersgill Cunliffe.

William was not a big man. I remember that in my twenties, his clothes fitted me exactly, which would have made him about 5ft. 7in. He had a very beautiful house and small farm, Springhead, behind the south downs near Steyning in West Sussex (an extremely lovely part of the country) that, according to Rudston, was not very profitable. William was a gentleman farmer rather than a working farmer, and Springhead's income, devastated by the farming recession in the late nineteenth century, was too small to support his lifestyle. Without farming knowledge to increase the profitability of the farm, William tried to supplement his income with a job procuring horses for the Army which required him to visit America each year, travelling west on the wagon trains to the rapidly-moving frontier. He had a small five-chambered revolver which remained in Rudston's possession until handed in to the police in an arms amnesty in the 1960's.

While in America, William met Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Christian Science movement, and became a firm disciple. This was certainly bad news for the farm, since, instead of getting on with the job he was supposed to be doing, he was wasting his time on the east coast of America with his new friends in the sect. Expenses may well have eroded much of any profit he might have made from these trips.

By contrast, Alice's parents, the Pickersgill-Cunliffes. were extremely well-to-do, and lived in a huge house that Rudston told me was modelled on Buckingham Palace. Rudston recalled visiting this house in fin-de-siecle days to stay with his grandmother Helen when he would have been about seven; his enjoyment of an extremely plush lifestyle, and his excitement at being allowed to ride on the box of the family's coach with the coachman. The Pickersgill Cunliffes produced no less than sixteen children, Rudston's mother Alice being the tenth in line. Possibly they might have gone on to produce more, but it was not to be -Alice's father was killed by a train on the London to Brighton railway line. Rudston said that this was as a result of ignoring a porter's advice that it was imprudent to wander across the line to chat to a friend, but his early death must have come as a devastating blow to his close-knit family.

The name Pickersgill Cunliffe is relatively new. It appears to have been first used in 1867 when John Cunliffe Pickersgill of Hooley Hall, Coulsdon, Surrey assumed the additional surname and arms of Cunliffe by Royal Licence (Burke's Landed Gentry 1972 page 270). The entry also tells us that he was born on the 28th March 1819, second son of John Pickersgill and Sophia, youngest daughter of John Cunliffe of High House, Addingham, Yorkshire. Hooley is a small village in the pass through the North Downs that carries both the slow and the fast London-Brighton railways on which Alice's father died as well as the main coast road. Alice was born in 1862, when John Pickersgill Cunliffe would have been in his early forties. He had already fathered nine children; even given an extreme rate of breeding of once every year, he would only have been around thirty when the first child appeared. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I think we must assume that John was Alice's father. It is also interesting to note that Alice was not born a Pickersgill Cunliffe. For the first five years of her life, she was simply Alice Pickersgill.

By 1891, the census shows that his widow Helen, described as living on her own means, had moved to Higham St Mary in Kent, just to the north of Tonbridge, at The Hermitage, 39 Hermitage Road with four of her daughters: Emily, Mary, Evelyn and Gertrude. The ménage was greatly outnumbered by their servants - eleven of them lived in various cottages and stables on the property. The census pre-dates Rudston's childhood visits by at least five years, so I think that The Hermitage must be the large house he remembers.

Alice moved to Springhead on her marriage to William. He was then 24; Alice only 20. I was told, I believe by Rudston's sister Faith, that Alice actually eloped with William. This may be true. They were married some time between July and September 1882 and the marriage was registered in Aylesford in Kent, some way from Alice's home. Although William appears to have been largely an absentee father in America, he did return home annually to ensure Alice's continuing pregnancy, and she produced a remarkable family of nine between 1883 and 1900. She therefore largely brought these children up herself, with the aid of another remarkable woman, a trained children's nurse who became her companion. This elegant and gracious lady had the grand names Edith Harriet Digby but was always known as the Lamb, a pet name widely used for companions of that era, and will be so called in the rest of this story. The Lamb came to Alice when she was 18, and remained with the family until she died in her eighties.

By 1891, the Springhead farm had failed and William (according to Rudston) had lost everything. He abandoned farming in favour of a job as a civilian musketry instructor of army recruits. William's new job was in Scarborough, the regiment's home base, so around 1891 the family rented East Ayton Lodge, a beautiful house at the head of the Forge Valley to the west of Scarborough in what is now the Yorkshire Moors National Park, standing in an 8-acre park of its own. The Lodge was to be a pied-a-terre for the family, for them to use during the building of a town house, 12 Southdene in the Fowthorpe area of Filey, which is on the south side of the town, near the golf course. Southdene was an elegant sweeping terrace of mock-Georgian design typical of many such developments in seaside resorts of the period. Examples are still to be seen in Brighton. The architect-designed frontage was erected by a speculative builder, and the remainder of each house completed to the design of the purchaser. It is said that the design of No.12 was produced by Alice herself. The even-numbered houses on the south side of Southdene, including No.12, were demolished many years ago.

Alice was probably pregnant with Rudston at the time of the cross-country move from West Sussex to North Yorkshire (he was born in January 1892) and seems to have farmed out her three older girls to families in the south over the period of the move. The 1891 census shows seven-year-old Rose as a visitor to the Rectory in Withyham, and six-year-old Barbara and five-year-old Marjorie were staying with their grandmother Helen at the Hermitage in Higham St. Mary. The three little ones, Joan, Faith and Elspeth, presumably made the move with their parents in the care of Alice and, of course the Lamb.

East Ayton Lodge was not a particularly large house for a staff of seven needed to cater for the needs of a family of eleven - two governesses, three indoor servants, a gardener/handyman and the Lamb. The family income was only £600 a year (just under £29,000 today; a reasonable income but not really enough to support what would have been known as a 'gentry house') so money was extremely tight. Alice's allowance for food, clothes and all housekeeping was only £1 a day (amazingly, worth £48.32 in today's money). Alice stretched this meagre budget to its limit by making all her children's clothes herself, and reputedly to professional standard. The seven girls were dressed alike in frocks, smart cloaks with matching tam o'shanters, with home-made undergarments; flannel next to the skin in the custom of the day, chemise, knickers (drawers) and two petticoats, one of which doubled as a flannel nightgown. A system of hand-me-down clothing was certainly in operation, and this was to cause considerable embarrassment to Rudston, as we shall see later in this story. Somehow or other, Alice also found the time to embroider a set of very beautiful fire screens, a painstaking art and one of the few things she did that she would have been trained to do before her marriage. Embroidery would have been considered a suitable leisure pursuit for a landed lady by her parents.

|

(Top) East Ayton Lodge as it would have appeared circa 1900. |

|

(Bottom) East Ayton Lodge as it is today; now a popular hotel. |

Rudston was therefore born into a family with too little money to support the lifestyle his father deemed necessary for a man who was probably already hoping to make a new career as an army officer. There is absolutely no doubt that the arrival of a son was greeted with great joy by Alice. Number seven was what she had longed for after six identically-clad daughters, and Rudston became her darling. They had a special relationship that was to last for the rest of Alice's life, although they were parted for many years.

Not surprisingly, the daughters, and particularly the bigger daughters, did not altogether share in their mother's joy at the new arrival. As small children will, Rudston was quick to spot and exploit his special status, and his earliest memory was of playing with his sisters on the front lawn and of uttering some strategic screams under his mother's window. Alice comforted the small boy with a chocolate bar which, when her back had retreated to a safe distance, was removed from him by Rose and shared between Elspeth and Faith.

Another early memory was of Marjorie, who would then have been a strapping lass of about eleven, putting the toddler on top of the heating boiler and abandoning him. He was, of course, too little to climb down by himself. I think it is safe to assume that the boiler was not working at the time. The small boy grew into a big man who never forgot this incident, and it would be recalled whenever he was in dispute with Marjorie, usually on a matter connected with religion. Take care what you do to a small child - they have long memories. To my shame, I challenged poor Marjorie with this tale when she was a very old lady. She said: 'Well, dear. I was trying to turn him into a little man'.

The family kept pigs, which fascinated Rudston. He was forbidden to visit them one day (for the very good reason that one of them was being slaughtered), and broke his nose falling off the bathroom stool he had climbed on to take a look at what was going on in the sties. This left him with an impaired sense of smell. He confided to me that, all his life, he had been totally unmoved by women's scents. They all smelled equally nasty to him.

On February 29th, 1896, Alice gave birth to another boy, William Edwin Cunliffe Fell. Alice's sister Mary, five years her senior, was staying at the Lodge to lend a hand. Rudston, Faith and Elspeth were talking quietly on the lawn, near their mother's window, and sensing that something important was happening. Aunt Mary broke the news, to Rudston's delight. He owned that he had longed for a baby brother. Sadly, little Edwin, always known as Dardy, had Down's Syndrome. He never learned to talk or walk, and died when only seven, before his birthday in 1904. Because the turn of a century is not a leap year except at a millennium, he therefore never had an official birthday. In spite of his disability, or perhaps because of it, he was very dear to Rudston, who dreaded the inevitable news of his death. Rudston, who started boarding school when Edwin was four, knew he would have to face the loss of Dardy alone, and a long way from home. Every letter Rudston wrote to his mother from Windsor asked lovingly after the little boy, with the pathetic hope that the news of him might be a little better.

The family's time at East Ayton Lodge was marred by further sadness, to add to the worries over Dardy. In Ayton churchyard, there is a memorial to Kate Town, one of their servants who died in 1893 at only 23, erected by William and Alice to commemorate "…eight years' faithful service". Kate had therefore been with them for most of their marriage and was only 15 when she entered their service.

Around 1896, close to the time of Dardy's birth, William joined the army as a dashing cavalry officer. Some of his career is documented in the quaint journalese of a newspaper clipping; unfortunately not dated but from its reference to the Boer war, probably printed some time in 1899:-

MAJOR FELL GOING TO SOUTH AFRICA

According to the Leeds Mercury, Major Fell, who was in charge of the military on the occasion of the Cronwright Schreiner disturbances at Scarborough, and who, when in Filey, successfully launched the Filey Golf Club, is going out to South Africa. About a year and a half ago, Major Fell was a civilian, holding office as musketry instructor to the troops at Scarborough. The exingencies of the war brought him to depot work in that place, and the excellent way he did it procured him the rank of captain. He was soon removed to York, where he attained his majority, and his work lay with the young soldiers before they were passed to the front. The splendid form of the men sent by him again attracted attention, with the result that his services are required at the front now. Probably, he will be heard of again. Even if not, he is remarkable as one of the very few men, outside the Royal circle, who have been Majors a year and a half after they were civilians.

Cronwright Schreiner was a pacifist, pro-Boer movement of the day, adhering to the feminist beliefs of the South African writer Olive Schreiner. For the army to have been involved, their 'disturbances' must have been very lively indeed! As the clipping tells us, William fought in the Boer war and indeed became Colonel of his regiment.

The family did not stay at East Ayton Lodge for very long. On the 1901 census, Alice gives their address as 12 South Dene, Filey, so they must have moved into their new town house some time between 1896 and 1900, when Honor was born. William is not shown on Alice's census, but was back in England and is listed in the census as a visitor of Edward A F W Herbert JP at Upper Helmsley Hall and as "living on own means ".

William, therefore, was once again away from his family when the 1901 census was taken, and there is something noteworthy about Alice's census return. Alice also states that she is "living on own means". This suggests that William was either unwilling or was no longer able to make any contribution at all to his family's maintenance, and it is therefore quite possible that 12 Southdene had been built with money from the very supportive Pickersgill-Cunliffe family and actually belonged to Alice.

In 1916, William died suddenly, from what appeared to be complications following a bout of influenza, and not, I was told by Rudston, at Filey. He was tended to the last by Elspeth, and therefore most probably died at Willerby Lodge near Staxton. Because of their shared religious beliefs, he was without benefit of any medical attention at all. This caused a very distressing national scandal at the time, as a death certificate could not be issued. His widow Alice was by then in her mid-fifties. Only Marjorie remained at home, and indeed was to stay with Alice until Alice died in 1952. The family, now marred by scandal, had all grown up and left home, so Alice (who seemed to prefer to live in town houses) moved back down south, to a five-bedroom terraced house in Eastbourne (97 Vicarage Road).

Alice did not have all her children at home. In her return for the 1901 census, her daughters Barbara, Marjorie, Joan and Elspeth, are shown as having being born at Pailness, and the next daughter Faith was born in Brighton. Only Edwin (East Ayton Lodge) and Honor (Filey) appear to have been born at home. Rudston does not appear on this census, as he was away at boarding school at the time, but his birth certificate gives his place of birth as Filey. Alice's first-born, Rose, is also missing from Alice's return as she was most likely in London, but her place of birth is given in the 1891 census as Brighton. In her census return, Alice gives her own place of birth as Pailness, a town or village I have been unable to find. The evidence is that she was born at Hooley Hall. Perhaps Hooley Hall and Pailness are one and the same? Further conjecture would suggest that the Brighton births took place in a hospital or clinic while Alice was visiting nearby Higham or Withyham. Rudston, born while the family was at East Ayton, was possibly also a hospital birth.

Alice therefore produced a family of eight children over a period of seventeen years, and largely brought them up on her own, to her own high Pickersgill Cunliffe standards. Marjorie indicated to me that they were forbidden to '…play with the village children down by the pond' so they were deprived of the companionship of children of their own age because of this class barrier. East Ayton is a small rural village so the family was very isolated at that time. In the absence of other friends, a three-way split developed in the family. The three big teenage girls tended to hang together and, perhaps, also tended to torment the little ones, Elspeth and Rudston. Faith and Joan formed a group on their own. Honor, arriving much later on the scene and indeed at a different address, became a loner. However, they became united in the feeling of superiority over others engendered in them by Alice, and were, in many ways, closer to each other than they were to their partners in marriage. Rose, Marjorie and Honor never married at all. There is also ample evidence of Rudston's special relationship with his mother. It is not too strong, I think, to say that he revered her. I have found it more difficult to define his relationship with his father. William could have been expected to have had a special interest in his only surviving son, and I suppose that it is possible that this explains why he left Rudston at Windsor after his voice trial, and also why, on one occasion, he abandoned the small boy at Waterloo with a guinea to make his own way to Windsor (rather a lot to give a small boy - a guinea in 1900 is worth about £50 today). These were, on the face of it, unkind acts, but maybe William thought that Rudston was becoming tied too tightly to his mother's apron strings and needed a sharp lesson in the value of independence.

William was away a lot in America, but wrote many letters to Rudston, sadly mostly concerned with his (William's) obsession with Christian Science. It must have all been rather confusing to the young Rudston. He obviously wanted to please his father, because he became a Christian Scientist himself, and indeed paid lip service to the Christian Science faith to the end, which was peculiar; to an engineer, some of its tenets must have seemed most unscientific. But he never refused his family medical attention, nor did he refuse it for himself at the end. He was not a regular attendee at his church, though he did attend for a short time in the nineteen forties. I went along with him on a couple of occasions to keep him company, but failed to be impressed. The point is that Rudston never made the slightest effort to convert me. Indeed, he attended the village church in Worlaby at the end of his life, and even wrote a regular feature in the Parish magazine. Both he and my mother had Christian burials. In fact, Rudston could not have been less like his father. Even in stature, Rudston failed to measure up by exceeding his father's height by five inches. He grew to be nearly six feet tall. In temperament, Rudston was very much closer to Alice.

Alice was a devout supported of the Church of England throughout her life, and it is hard to imagine a very close relationship between a husband and wife with such diametrically opposed beliefs. I think there are strong signs that this was transmitted to the children, another factor that caused the family to become polarised. In her old age, Honor confided to my sister-in-law Catherine something of the horror she felt as a child at being pulled in two different directions by her parents; an experience which left her a self-confessed atheist, though I came to regard her as a deeply spiritual person. Maybe times have changed, and beliefs are not so passionately held today as they were at the turn of the century. There might have been problems in this family even if William had never met Mary Baker Eddy. Rose favoured the High Anglican church, unchanged from the time of Henry VIII, and there was always bad feeling between her and Marjorie over whether seven sacraments are needed for salvation, or only two!

|

Rudston aged about ten. The picture was taken by his father, William Fell, during one of Rudston's holidays from Windsor, and probably at 12 Southdene. The little girl was to become Dame Honor, FRS, one of the world's leading cytologists. |

The tradition of caring for those who served the family, and providing for their old age, was at that time continued by the Fells, and Miss Jefferson, Elspeth's companion, was even given a small income from a family legacy and occupied Rose's Eastbourne house after Rose died. When Alice moved to Eastbourne with Marjorie, her companion the Lamb went to Cambridge and spent the rest of her life caring for Honor.

Alice remained physically and mentally active throughout the remainder of her long and useful life, though she did suffer from the pain of angina in her final years. She was perfectly able to walk, her cane being more of a stage prop than a physical one, and this was perhaps not fully appreciated by her son-in-law Francis, who hired an electric wheel chair for a wartime visit to his small estate at Willerby near Filey. The idea was to give the old lady mobility. With her considerable practical talents, Alice immediately mastered the simple controls and set off at full speed, thoroughly enjoying the new experience of driving something. A few minutes later, Francis was horrified to see her slumped forward, apparently motionless, at the entrance to the estate and raced over to be told with some asperity: 'I was merely opening the gate to go into the village!'

I met two of the Pickersgill-Cunliffe girls in Eastbourne in 1951, when they were both old ladies. One was great-aunt Millicent, the youngest of the children and then 79; the other Alice herself, who was 88. Both were ramrod-straight old ladies, reminiscent of the elderly Queen Victoria down to small details of dress (Alice never abandoned her widow's weeds). What came across to me was their very great kindness, and interest in me as a person. I did feel the need, though, to be very much on my best behaviour, and found myself, at first, frantically searching my mind for recollection of the few small social graces I might have learned as a child. Later, with my grandmother Alice, I overcame this fear and grew to love her. She was indeed a very remarkable and talented woman. There was, though, an echo of her father in her approach to Eastbourne traffic. When she wanted to cross the road, she simply raised her black, silver-topped cane in the air and stepped off the pavement, totally oblivious to the screech of tortured rubber and imprecations of drivers. The family did try to remonstrate with her, but all she said was: 'Oh but dear! They always stop for ME!'

Alice, then, was a product of a system that had its roots firmly in the great houses so vividly described by Jane Austen. Like all the daughters of these houses, she would have been carefully schooled in music, behaviour, conversation, dress and entertainment; all attributes cultivated to ensure that she would make a 'good' marriage and be able to support her husband in his role as absolute head of her family. Marketable talents would not have been encouraged, as they would have been perceived as pointless and even threatening to potential partners. Alice's later accomplishments were to go far beyond this limited training. She became an amateur architect of considerable skill, designing her daughter Rose's cottage in the village of Staxton near Scarborough as well as the family house in Filey, an excellent seamstress, a prudent housekeeper and, according to her daughter Marjorie, no mean performer with a screwdriver at do-it-yourself jobs around the house. Hard times were to come in her life, and she was destined to become the effective head of her family. She was a very remarkable and talented woman; had she been born fifty years later, she would undoubtedly have become eminent.

I lived in Rose's cottage in Staxton when I was a child, and in fact visited it quite recently. Amateur architecture often fails to achieve balanced proportions, but Rose's cottage is beautifully proportioned and in fact very pretty. It hides a secret that represented ground-breaking technology at the time. Alice had designed all three chimney stacks into the centre of the building rather than placing them on outside walls. Her reasoning was that this would add strength to the building, and also conserve heat that would otherwise be wasted to the outside air. This ecological thinking was unheard of in the 1920's when the cottage was built.

In some ways Rudston's childhood ended in 1900, when he started boarding at Windsor. Later, while an apprentice, Rudston actually built some sort of a car at the Filey house, which was upholstered by his mother. Otherwise, Filey played little or no further part in his life. But his sisters all manifested excellence in their own ways; a great tribute to their upbringing by Alice and her companion. As relatives, they surely deserve a mention.

Rose, the firstborn, was a very talented amateur artist with a flamboyant style in watercolours. She never married, staying close to her family all her life. She was a VAD in the 1914-18 war, and spent most of her working life as a district nurse in the very poor areas of London's East End. She ran a soup kitchen during the great depression. She moved to the village of Staxton, near Scarborough just before the last war, to be close to her married sister Elspeth. My brother and I lived in her pretty little house in 1940, and I have such happy memories of my time there. Rose, known as bunny, spoilt me outrageously and organised the sort of outings into the gorgeous countryside that every small boy should be able to remember. She made the most superb soup on her kitchen range, served in pretty blue-and-white striped crockery. Rose was a devout High Anglican, a church with direct roots to Henry VIII and therefore a sort of Catholic Church without a pope. When Elspeth's husband retired, the family (including Aunt Rose) moved to Eastbourne so that, with the exception of Rudston, they were all together at the end.

Barbara was married to a Church of England curate. Her death soon after was very tragic. Elspeth's husband, Francis, had had a new part made for the steering of his touring car by a local garage. They used mild steel rather than toughened steel (probably the best they could do with the tools they had) and the part failed. The car crashed, and Barbara was thrown out, over a hedge and into a cow field. I believe her only injury was a bad gash to her thigh from the windscreen support, but it proved fatal. Gangrene set in and she died after considerable suffering.

Rudston carried a resentment against Marjorie almost until the end of his days, and it was to do with the boiler incident. Throughout her life, poor Marjorie only had to say a wrong word (usually about religion) and the incident would be recalled. I recall the family gathering after his beloved sister Elspeth's funeral, when Marjorie made what was no more than a mildly critical remark about the humanistic nature of the service. Rudston was so deeply distressed that he had to leave the room.

In fact, Marjorie was an extremely intelligent, well-read woman, and dedicated her whole life to the welfare of others. Born a quarter of a century later, she would have made an excellent MP or missionary priest. She followed her mother's religion, and lived with her mother until Alice died. I week-ended with Alice and Marjorie at 97 Vicarage Road when I was a student in Brighton in 1951, and it was Marjorie who paid for my driving lessons.

Marjorie was a great evangelist, not only for her faith but also for her standards. Hearing that class was dead, she remarked:- 'Then I must educate these poor people to my standards - I won't descend to theirs'. She used to detain tradesmen with sweets while she lectured them on propriety, and even managed to persuade one to have his children baptised. Even she was disconcerted when he asked if he could marry his lady at the same ceremony. Poor to Marjorie, by the way, meant poor in spirit. It had nothing to do with cash flow.

All her life, Marjorie had heart problems caused by a defective mitral valve - a legacy of childhood rheumatic fever - yet right to the end she was shopping for a 'poor' old lady who turned out to be twelve years younger than she was. She died of arteriosclerosis, which affected her mind at the end. If Marjorie had a fault, it was that she tended to be rather thick-skinned. She saw criticism as a fault in the critic rather than in herself. Who am I to say that she was wrong?

Faith was regarded as the eccentric of the family. Personally, I think this sells her short - but then, maybe I am regarded as the eccentric in mine. She was Slade-trained, and was a professional artist of very considerable merit. Her work in oils is superb, but she was not afraid to experiment in any medium. She had a wild and rebellious youth (an Italian waiter is darkly mentioned) before settling to a childless marriage with William Walker, an Oundle housemaster, a kind if rather stuffy man of whom I have nothing but the fondest memories. He really was a perfect gentleman, although I do feel that Aunt Faith's antics, particularly her total absence of any sense of time, left him clinging to the ceiling by his fingernails on occasion. When William retired, they moved to The Tanneries in the lovely village of Alfriston near Eastbourne.

In some ways, William's death seemed to set Faith free. The old lady began an intensely creative period, and practised her art precisely when she felt like it, even if it was 3 a.m. when the muse struck. This caused her sisters immense consternation, I remember. They moved her into a new maisonette under her sister Elspeth's eye. I couldn't see why, with William's rather autocratic control gone, the old lass couldn't please herself when she got up and went to bed. She was a diabetic, and confessed to me that she loved a slice of fruit cake as it gave her a 'high' very similar to drink. She also was not ashamed to own her sexuality. 'Just because you're old, dear, it doesn't mean the feelings go away. It's just that it doesn't seem quite proper to do anything about them'. Faith was a cheerful agnostic to the end and, in many ways, my favourite.

One of the nice things about all the aunts was the way they remembered Henry and me at Christmas with little presents they had procured through the year; in the case of Rose and Marjorie, on very limited budgets. I recall receiving a very acceptable and mature present from Faith for Christmas 1946. Henry got the 'Boy's Book of Farming'. I can't recall whether he had his NDA with Gold Medal or not at the time.

Joan seemed to find it easier than the other children to sever the cord that bound this incredibly close family together. She married Jack Mann, a Dubliner with immense charm and a thoroughly nice man, and had three children. Her boys emigrated to Canada, where both are highly successful, and her daughter Alice married a soldier, also a very fine person. I had a soft spot for Alice when I was young. I considered her incredibly beautiful, which indeed she was. Rose described her as 'a beautiful lily'. I remember staying with Alice and her husband when they were first married, in a lovely house in Guildford, and doing a lot of gardening. I only met Joan near the end, when she was dying of cancer. I remember her as a very nice person, thoroughly deserving of her charming family.

Elspeth was very strong-minded and multi-talented; a reasonably accomplished violinist and an excellent amateur watercolour artist. Her style was romantic rather than flamboyant. But Elspeth's real power lay in her talent for thinking in three dimensions. She always had what she called her studio, with fret saw and other woodworking tools, where she would create jigsaw puzzles and working toys out of odd bits of wood, without benefit of working drawings. The ideas seemed to flow straight from her mind into the finished object. She was good enough at her craft to obtain commissions from Chad Valley for toys, and from various publishers for book illustration. My brother still has one of her jigsaws. It is a wonderful creation in which every interlocking piece is a complete real or fanciful creature - a flower, fish, gnome or fairy. She was a great strength in the family. In childhood, she and Rudston were unusually close, and this bond persisted right through their lives. Rudston loved this sister above all others.

Elspeth married Francis Eagle-Clarke, a Filey solicitor, and lived with him at Willerby Lodge, a hunting lodge near Staxton. They had one daughter, Una, who married MG's pre-war racing driver Goldie Gardner. Una and Goldie lived in Eastbourne and had a daughter, Rosalind. After Goldie's death, Una became Mayor of Eastbourne for a time.

Elspeth died in Eastbourne, again without benefit of medical attention as she had followed her father into Christian Science, but times had changed and there was no problem in obtaining a death certificate without autopsy for someone so obviously deceased from terminal cancer.

Honor was born in 1900. She was a solitary and, by her own account, appallingly scruffy child. Everyone else was just about grown up. Mother and the Lamb had their hands full with coping with Dardy, so Honor was told to '-go and play in the garden. And for goodness' sake, stay away from the front of the house!' This suited her perfectly. She had a little oilskin rain hat which tied under her chin. This was a dear possession, as she had found that, turned inside out and inverted, it made the perfect conveyance for the tadpoles and newts she imported into her bedroom. At thirteen, she stopped the show at her sister Barbara's wedding by turning up with a ferret on her shoulder. I don't think she ever really understood the family's consternation. To Honor, everybody clearly loved ferrets (and indeed all creatures) as much as she did. Janie, the ferret in question, was, to Honor, totally acceptable as she had taken the trouble to shampoo her for the occasion. This love of creatures was to persist all her life. A portrait by Faith of Honor as a young woman includes a ferret on her shoulder. Although animals were used in her work, she had a passionate belief that far too many are used in experiments, and rigidly regulated their use, as well as their welfare, in her own laboratories. In this regard, she probably did far more for animal rights than the activists can ever hope to achieve.

Honor was a pure rather than an applied scientist, and therefore spent her life breaking new ground. She retained until her death a total commitment to her experiments, with a fresh adrenalin 'high' each time they began to work. This nearly caused her end at Strangeways Laboratory. Reaching absently for a liver sausage sandwich (made for her by the Lamb and strictly forbidden, of course, in the culture environment of a biological laboratory), she applied her eye to the microscope and ascribed the tingle she felt to the excitement that always possessed her when an experiment was going well. The next person to use the microscope ended up on the other side of the room. It turned out that the laboratory technician had wired up the mains plug incorrectly, and the full mains voltage was available at the eyepiece.

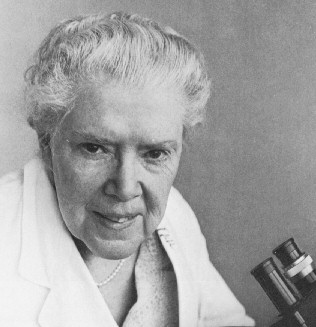

Honor was educated at Wychwood School, Oxford and in 1916 went to Madras College, St. Andrews before graduating from Edinburgh University with B.Sc, Ph.D and ultimately D.Sc. She was the first woman to become a Fellow of the Royal Society, and became director of Strangeways laboratory, Cambridge in 1929 - an extraordinary achievement for a woman in that era. She was awarded her DBE for services to cytology. Dame Honor is always remembered by her peers as an exceptionally smart woman, who dressed in stylish if slightly old-fashioned suits. In fact, she claimed to have absolutely no dress sense whatever. The Lamb had perfect dress sense, and taught Honor some basic rules of what went with what. Although Honor lost guidance of style change at the Lamb's death, she retained enough of the basic rules to keep her looking extremely smart to the end of her days.

Honor belonged to the great fellowship of scientists that recognises no boundaries of sex, politics or nationality. She was welcomed and revered throughout the world. She lived rather frugally in Cambridge, where I visited her once in the forties with Rudston. I think she was regarded with some awe by her brother and sisters and saw little of them through the year, though she spent her holidays with one or other of the sisters and always attended the family Christmas. In her final years, she visited my brother Henry regularly and formed a great love for the Lincolnshire wolds.

It was only at the very end that I was privileged to see what a great woman she was, and how deep a love and understanding she had of her family as well as of mankind as a whole. She was still working, although in her eighties, and was taken ill on her return from a lecture tour in America. She was admitted to Addenbrookes, who diagnosed her oesophageal cancer. At that time, I was on contract in London, living in Humberside, and formed the habit of calling as I passed through Cambridge. For some reason, she felt able to talk freely, and it is to her that I owe some of the material in this book. Far from being unaware, except in matters of science, I discovered that she knew us all inside out, warts and all.

Honor claimed to be an atheist, though I prefer to regard her as a humanist, and the manner of her passing must be recorded. Before she was told of her terminal condition, she called frequent meetings to ensure her current work could remain on hold until her return. When told that she was dying, she rejected a bypass operation to relieve her pain and accepted that this was the end. She had one more meeting with her staff to hand over her work, and a meeting with her solicitor to set her affairs in order. Then she gave herself permission to die, which she did a few hours later.

Honor loved her brother unconditionally, despite faults in him that she perceived. I was talking about his apparent lack of interest in worldly acclaim, and she corrected me: 'Oh, no, John. He had his vanities too'. She was right. Rudston was a good man - but he needed to be seen as a good man. That is not a very serious shortcoming.

|

Dame Honor Fell, FRS shortly before her death - still working in her eighties. |

Honor's last words to me were:- 'Never be afraid of solitude, John. It's not at all the same thing as loneliness.' The words meant little at the time. A few years later, they were to be the beacon that guided me through my own particular dark tunnel. What a wonderful legacy from an aunt that I loved dearly.

<< Introduction • End of Chapter 1 • Chapter 2 >>