CHAPTER TWO

School Days

Vivat! Vivat! Vivat!

Rudston's primary education was gained as a chorister at the choir school of the royal chapel at Windsor. I suppose that Windsor must be one of the most exciting schools of all to attend. The chapel is frequently home to the greatest in the land, especially, of course, the Garter Knights; all on their very best behaviour as they are there at the special invitation of the monarch. A perk of the choristers' jobs is spur money, a fine they impose on anybody imprudent enough to enter the chapel without taking off his spurs. The fine is paid to the sharp-eyed chorister lucky enough to spot the offender - but only after the chorister has established his credentials by repeating his gamut (singing a musical scale). It's quite big money, too - about £10 today. Henry VII and VIII both had to pay this fine, and the system is still operative today. I have no record of Rudston ever scoring a hit with this one. But Windsor certainly scored a hit with him. He spoke of his time there with love for the remainder of his life.

My brother Henry has in his possession a clock. It is a rather ugly clock. The works came from a far more valuable piece - a French black marble clock that was dropped and broken. The replacement oak case was made by Rudston during his retirement, from a piece of medieval beam he obtained from the Chapel Royal, Windsor. He scrounged it from a workman engaged in restoration work during his time at Windsor, and treasured it all his life. The fact that a schoolboy would do that tells us a great deal about Rudston.

Before puberty, Rudston had an exceptional singing voice, and was accepted into the choir school at Windsor as a boarder at the age of eight. William took him for his voice trial, suitably dressed in miniature officer's uniform with a forage cap. They broke the long journey from Filey to Windsor with an overnight stay on May 21st, 1900 at the King's Cross hotel. Rudston had an overnight bag containing a reach-me-down nightie; a petticoat which had belonged to one of his sisters and was very obviously feminine. The next day, Rudston was interviewed by the formidable Sir Walter Parratt, organist and Master of the Queen's Musick, as well as by the headmaster Herman Dean. Rudston's choice of test piece was the hymn 'There is a green hill', and Sir Walter accompanied with three different tunes, none of which Rudston had heard before. This was almost certainly part of the test; Sir Walter was checking not only the quality of Rudston's voice but also his ability to learn new music. Rudston remembered both men as being kind and reassuring throughout.

The small boy had expected to return home after the voice test, but William persuaded Dean to accept the boy into school immediately, for the remainder of the summer term. Alice was not consulted and indeed was horrified when William returned empty-handed - Rudston had no school clothes with him, and there was also the matter of that dreadful nightie.

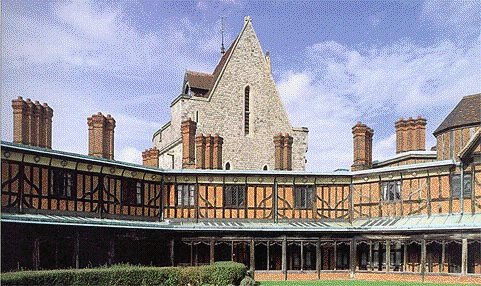

The Horseshoe Cloisters at Windsor, where the young Rudston

boarded with the other choristers and clergy.

The fifteenth century building is still used for this purpose today.

Windsor choir school, like all major schools of its kind, has to impose a harsh regime that has its roots in Elizabethan times. The boys not only have to practice for several hours a day, but also have to prepare for the tough examinations needed for entry to major public schools. Russell Thorndike, brother of Dame Sybil, was there in Rudston's time, though he was a few years older. He has written a book, Children of the Garter, describing his school days in detail, and it is well worth reading. However, the men Thorndike found harsh and overbearing, in particular Sir Walter, Rudston found helpful and interested in him because, like them, Rudston was a perfectionist in his music. Rudston claimed that the choir was the best in the land, but I have to say that the same claim is made for King's College, Cambridge and also by the choristers of Winchester Cathedral. Anyway, I had a reasonable voice at the same age, and I happen to know that my choir was the best. Let us compromise and say that the standards at Windsor are exceptionally high. They have to be. The choir sings at major state events.

Choirmasters are a breed apart. The musical and behavioural discipline of the treble line of a great choir, boys aged between around 8 to 13, is not an accident of nature. Choirmasters are not only superb musicians, but also strict disciplinarians. They can also manifest a degree of irascibility. It was clear that Sir Walter was aware of a tendency to go over the top by his apologetic riddle to the choir school after a major row: 'Why am I like the Mediterranean Sea? Because our storms are sudden but don't last long'. (Almost fifty years later, my own choirmaster was of the same ilk, made worse by the fact that he liked his pint on a Saturday night. The resultant Sunday morning hangover could make attitudes at choir rehearsal unpredictable. But we loved him because of his ability to create beauty from a collection of scruffy boys.)

Thorndike was about three years older than Rudston, and took the little boy under his wing. Rudston bears testimony to this in his very first letter to his mother, dated May 23rd, 1900:

My dear mother,

I think the school is very nice, and the boys are very nice. They are so kind. All the boys said it was very good to be able to get in the afternoon that I was tried. There is one boy, Russell Thorndike, who said if any boy was unkind to me I could tell him and he said he had a friend who wanted to like me, he likes me too. Yesterday Miss Fox gave me a bowl of bread and milk, to make my cold better.

Your loving son, Rudston.

This letter, curiously mature and reassuring for an eight-year-old, was the first of many Rudston wrote to Alice. I have no record of any he wrote to William.

Rudston loved Windsor and every minute he spent there. It was at Windsor that he formed his great and abiding love, not only for ancient buildings but for the pipe organ. His interest in organ music showed itself not only in the sound the instrument made, but in the mechanisms by which it made it. It is unusual for a boy of his age to have befriended, not only the choir master and organist, but also the artisans who visited Windsor to restore and maintain the artefacts he was learning to love. The dates on some of his books on organ building and organ tuning show that he acquired them during his stay at Windsor. He was only there, of course, between the ages of eight and thirteen (1900-1905).

|

The choir stalls in St. George's Chapel, Windsor, one of which was occupied by Rudston at every service during his time as a chorister, including the funeral of Queen Victoria. Although the picture is contemporary, the chapel is exactly as it was at the turn of the last century. |

Rudston's letters to his mother are enthusiastic and newsy, showing a boy that was turning outwards. He made many friends, including the great Dr. Henry Lee, subsequently to become organist at Westminster. Rudston and I called on Dr. Henry in 1952, after he had retired to Devon. He had a club foot, so how he managed intricate pedal passages I cannot say. He was precocious at Windsor, and frequently played at choir practice to allow Sir Walter to concentrate on the job of banging the boys' heads together.

Rudston's knack of being in the right place at the right time certainly showed itself at Windsor. He sang both at the funeral of Victoria and at Edward VII's coronation. The funeral was not too bad, as the service was in the Chapel Royal. He told me that there was a near-disaster with the gun carriage. There is a steep hill to the chapel, and it was an icy day. The horses lost their footing and bolted, very nearly depositing Victoria on the road. The naval detachment that formed part of the procession came to the rescue with ropes, and manhandled the gun carriage up to the west door of the chapel.

Victoria, therefore, was delivered to the Chapel by hand and, ever since, naval ratings have always pulled the gun carriage at state funerals.

The coronation in Westminster Abbey was far more of an ordeal. It involved endless rehearsals, keeping the boys captive for hours on end without the chance of using the lavatory. Then the King was taken ill with appendicitis, and the whole thing was cancelled. By the time the King was well enough to be crowned, Rudston recalled, the decorations in the Abbey were beginning to look decidedly tatty. The day itself was horrendous, as it meant the boys having to stay in their places for six hours. It would be nice to be able to tell readers about the ceremony itself, but I have no data. All Rudston recalled of the day was bursting to go to the lavatory.

Rudston sang at one more state event, which was the wedding of Victoria's grand daughter Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone. He recalled her as a very beautiful young woman and the wedding itself as a very happy occasion. Towards the end of his life, she appeared on television as a very old lady indeed. Rudston wrote to her, saying that he still remembered her as a very beautiful bride and sending her his pink memorial card of the wedding, and had a charming reply in her own handwriting.

Towards the end of his time in Windsor, Rudston's letters home repeatedly asked if William had done anything about entering him into a public school. In the event, William did nothing until Rudston had actually left, by which time the only choice available was Tonbridge. Tonbridge is only about a mile away from Higham, which leads to the conjecture (unprovable now, of course) that William, who by 1904 had no funds left, did nothing about the matter at all, and that it was the Pickersgill Cunliffes who saved the day.

I have no record of how well Rudston did in his Common Entrance examination, nor of his preference for secondary education if choice of school had been available. What I do know for certain is that Rudston cordially detested Tonbridge, and hated every minute he spent there. I really don't know why, as Tonbridge is regarded as a good school, but perhaps it is because Tonbridge is sports-oriented, and Rudston was not a good sportsman. Also, he had at puberty begun to suffer from a minor, easily-correctable condition which made it extremely difficult for him to urinate and probably caused him pain at other times. Amazingly, perhaps because of his Christian Science beliefs, he did not have the condition corrected until he was in his early thirties. This condition made long journeys in the non-corridor trains of the era sheer purgatory to him.

Anyway, whatever the reason, what happened next is a turning point in the story. His father was a Lieutenant Colonel in a cavalry regiment, and logically Rudston should have stayed at Tonbridge until he was eighteen. He would then have been welcomed into his father's regiment with a commission. Had this happened, this story could not have been written.

In fact, Rudston left Tonbridge in 1907, when he was only fifteen, to begin his engineering apprenticeship. It was almost unheard of for a public school boy to follow such a course at his age, and Rudston made it quite clear to me that the move was made with the full support of his mother Alice. When war broke out in 1914, Rudston avoided not only his father's regiment but the army altogether, preferring to enter the navy as a rating. Subsequently, he transferred to the RFC where he received his commission.

Musically, it is a pity that Rudston was such a perfectionist. Like me, his voice was mediocre after it broke, but it was quite good enough for him to have enjoyed church music in a choir. Also like me, he had little keyboard skill so never really played the organ. He had been taught some basic improvisation while at Windsor and left it at that. I am bound to say that I think he denied himself a lot of pleasure, simply because he knew he could never be a Dr. Henry Lee. Neither can I, but I don't let it stop me.

<< Chapter 1 • End of Chapter 2 • Chapter 3 >>